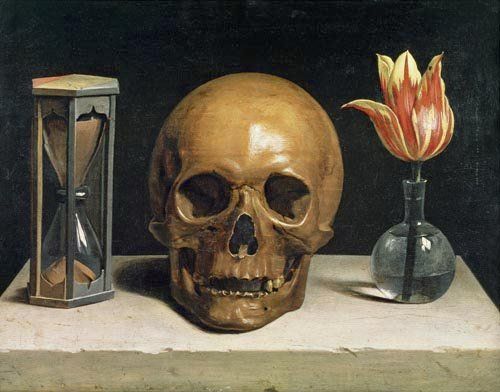

Life is short. It’s ticking away and seems to me that it passes by faster as we get older. Memento mori hasn’t got to do with morbidity or promoting fear, but inspiring, motivating and clarifying the individual’s life. Thinking about death not only reminds us that we have a limited amount of time to do the things we want to do, it also teaches us to accept the reality of death itself and that it’s all around us. Memento mori is Latin for remember thou art mortal. In the famous painting by Philippe de Champaigne from 1671, you see the three essentials of memento mori.

The hourglass stands for the notion that life is ticking away second after second. The rose stands for the truth about vitality, which is that, at some point, we all decay. The skull represents death. We are going to die, not only us, the people around us including our loved ones as well. This means that today could be the last day you walk this earth.

“You could leave life right now. Let that determine what you do and say and think,” wrote Marcus Aurelius in his meditations. So, if you’d die today, what would you do? Some people would certainly go on satisfying their hedonic needs, getting whatever pleasure they can think of. According to stoic principles, that would not be a preferred option. Rather, you’d probably live your last hours as virtuously as possible. Do you want to show appreciation for your loved ones? Tell them you love them. Do you have unfinished business? Now is the time to take care of that. So memento mori is a great antidote to one of the nastiest habits of mankind: procrastination. Procrastination can only take place if we believe that we have an abundance of time. When we take that belief away, we face the necessity of doing our task now, because tomorrow we might be gone. Thinking about it may evoke feelings of fear and sorrow along with the motivation to take care of our business. This isn’t caused by death itself but by our mindset towards it.

Here is a quote by Epictetus:

“Men are disturbed, not by things, but by the principles and notions which they form concerning things. Death for instance, is not terrible, else it would have appeared so to Socrates. But the terror consists in our notion of death that it is terrible.”

When we stop fearing death and we see it as nothing more than an unbeatable consequence of life, we can be appreciative for the time that is given to us and not waste it doing petty things. Another dimension of memento mori is preparation. Yes, we will lose the people we love and sometimes in the most brutal ways. Not being affected by loss is, of course, easier said than done. Even though the stoics propose this ideal, most of us are still human and will have to deal with grief when someone we love dies. Remind ourselves of the possibility that we can lose a loved one as we speak, helps us to be less shocked when that happens. For most people I know, losing someone they love is excruciating. Humans are often so attached to each other that they cannot bear the loss, but if we are mindful of the truth, we can cultivate a healthier mindset towards the possibility of loss. Instead of clinging to a person, wishing that we will never get separated, we can embrace the reality that the day of separation will come. This doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t grieve and mourn. It means that we are prepared all along. We can be more functional and helpful human beings for the community when this occurs. In this case losing someone due to mortality becomes more neutral.

Here’s how Marcus Aurelius puts it:

“Don’t look down on death, but welcome it. It too is one of the things required by nature. Like youth and old age. Like growth and maturity. Like a new set of teeth, a beard, the first gray hair. Like sex and pregnancy and childbirth. Like all the other physical changes at each stage of life, our dissolution is no different.”

What happens after we pass away? No one knows for sure, but what we do know is that mortality is upon us.

When death smiles at us, is there a better response than to smile back?